Main Content

Although we have thousands of extant (currently living) reptiles around the globe, there are many interesting extinct ones as well! Here are just a sampling of some of the amazing fossils that have been found of extinct reptiles!

Titanoboa model on display. See the humans in the background for a comparison in size. Photo from Ryan Sommma/flickr.

Titanoboa

The 50-Foot Prehistoric Snake

Article from https://allthatsinteresting.com/Titanoboa-snake

Some five million years after the extinction of the dinosaurs there left a vacuum at the top of the food chain. Titanoboa gladly stepped up. Titanoboa, the enormous serpent of legend, thrived in the tropical jungles of South America. This prehistoric species grew up to 50 feet in length and weighed as much as 2,500 pounds. That’s as long as a semitrailer you see on highways and about twice as heavy as a polar bear. At its thickest point, Titanoboa was three feet wide, which is longer than a human arm. Some scientists think it killed by constricting and asphyxiating its prey, while others argue that though it looked like a boa constrictor (the resemblance that gave it its name), it behaved like an anaconda, lurking in the shallows and ambushing unsuspecting animals with a stunning blow. Scientists do agree that the great snake swallowed its giant prey whole.

Titanoboa is a shockingly recent discovery. The story of its reappearance began in 2002 when a student uncovered a fossilized leaf on a visit to the massive coal mine at Cerrejón in Colombia. The discovery was an intriguing one: it suggested that once upon a time, the area had been home to a sprawling jungle. Further study revealed that the fossil belonged to the Paleocene era — which meant the mine might once have been the site of one of the world’s first rainforests. More digging uncovered remarkable specimens: giant turtles and crocodiles, and some of the first bananas, avocados, and bean plants that ever sprouted on planet earth.

They also uncovered a massive vertebra — a vertebra far too large to belong to any jungle serpent on record. It was an incredible find, and researchers immediately began combing the mines for more fragments of the jungle titan. Their working theory was that the massive snake to which the vertebra belonged had been caught in a mudslide that buried it. Millions of years and dozens of feet of rock later, the bone became part of rich coal fields — which meant there might be others nearby.

Remarkably, over the next few years, the team uncovered the remains of 28 enormous serpents and not one but three skull fragments, allowing them to piece together a full-scale replica of a snake so large and so frightening that it left no doubt about its place in the new jungles of the world. Even among the massive creatures of the ancient rainforest, Titanoboa was king: it was the apex predator of its era, a creature as unquestionably the ruler of its environment as the Tyrannosaurus Rex was in its own time. Until Titanoboa’s discovery, the largest snake fossil ever found came in at 33 feet and weighed 1,000 pounds. That was Gigantophis, a snake that lived 20 million years ago in Africa.

The largest snake species today is the giant anaconda, and it can grow to around 15 feet in length — less than one-third of the size of your average Titanoboa. Anacondas rarely reach more than 20 feet in length or weigh more than 500 pounds.

Megalania prisca

Giant Monitor Lizard

Article from https://australianmuseum.net.au/learn/australia-over-time/extinct-animals/megalania-prisca/

Megalania prisca, the largest terrestrial lizard known, was a giant goanna (monitor lizard). First described from the Darling Downs in Queensland by Sir Richard Owen in 1859, Megalania lived in a variety of eastern Australian Pleistocene habitats – open forests, woodlands and perhaps grasslands. Megalania would have been a formidable reptilian predator like its relative the Komodo Dragon of Indonesia, and may have eaten large mammals, snakes, other reptiles and birds.

Megalania prisca was an enormous monitor lizard – up to 5 meters long – with an unusual crest on its snout (a smaller but similar crest is also seen in the perentie, Varanus giganateus and in other Australian species). The teeth of Megalania were sharp and recurved with wrinkled, infolded enamel. Megalania had small bones (osteoderms) embedded in the skin of the snout and nape of the neck.

Megalania lived in a broad range of Pleistocene habitats, including open forests, woodlands and perhaps grasslands. While some fossils have been found in stream, river deposits as well and caves, it is rare, and was probably not living in those areas. Megalania was widely distributed across much of eastern Australia although complete fossils are rare. The closest relatives of Megalania are other goannas or monitor lizards (Varanidae).

Remains of Megalania have often been found with fossils of large animals like kangaroos, suggesting that Megalania may have taken large prey, like the ora or Komodo Dragon. Living oras consume large mammals, including deer, wild pigs and goats. Like other varanids, Megalania may have been an ambush predator/scavenger whose toxic saliva would have caused infection and death to its victims. In spite of its large size, Megalania would have needed much less to eat than a mammalian predator of comparable size.

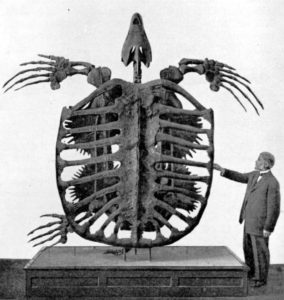

Archelon

Info from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archelon

Archelon is an extinct marine turtle from the Late Cretaceous, and is the largest turtle ever to have been documented, with the biggest specimen measuring 460 cm (15 ft) from head to tail, 400 cm (13 ft) from flipper to flipper, and 2,200 kg (4,900 lb) in weight. The leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) was once thought to be its closest living relative, but now, Protostegidae is thought to be a completely separate lineage from any living sea turtle.

Archelon had a leathery carapace instead of the hard shell seen in sea turtles. The carapace may have featured a row of small ridges each peaking at 2.5 or 5 cm (1 or 2 in) in height. It had an especially hooked beak and it jaws were adept at crushing, so its diet probably consisted of hard-shelled crustaceans and mollusks while slowly moving over the seafloor. However, its beak may have been adapted for shearing flesh, and Archelon was likely able to produce powerful strokes necessary for open-ocean travel. It inhabited the northern Western Interior Seaway, a mild to cool area dominated by plesiosaurs, hesperornithiform seabirds, and mosasaurs. It may have gone extinct due to the shrinking of the seaway, increased egg and hatchling predation, and cooling climate.

Archelon was an obligate carnivore. The thick plastron indicates the animal probably spent a lot of time on the soft, muddy seafloor, likely a slow-moving bottom feeder. According to American paleontologist Samuel Wendell Williston, the jaws were adapted for crushing, implying the turtle ate large mollusks and crustaceans. Conversely, the beak may have been adapted for shearing flesh, and it might have been able to target larger fish and reptiles, as well as soft-bodied creatures, similar to the leatherback sea turtle, such as squid and jellyfish. However, it is possible the sharp beak was used only in combat against other Archelon. The nautilus Eutrephoceras dekayi was found in great number near an Archelon specimen, and may have been a potential food source. Archelon may have also occasionally scavenged off the surface water. Archelon, like other marine turtles, probably would have had to have come onshore to nest; like other turtles, it probably dug out a hollow in the sand, laid several dozens of eggs, and took no part in child rearing.

By Sara Ruane, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Rutgers University-Newark, and Lisa Rothenburger, County 4-H Agent, Rutgers Cooperative Extension